Talk given at Our Criminal Past: Digitisation, Social Media and Crime History Workshop, London Metropolitan Archives, 17 May 2013

My academic apprenticeship, in Aberystwyth, was spent engrossed in two things: first, early modern Welsh and northern English crime archives, and second, the potential of the Internet for research and teaching and simply opening up early modern history to as many people as possible. That wasn’t a completely respectable interest back in 1999, and I’m still amazed sometimes that I’ve been able to spend I’ve spent the last 7 years indulging shamelessly in that obsession and get paid for it.

But what about the first of my obsessions? A couple of weeks ago, the Financial Times told us that more cranes have been erected in London in the past 3 years than everywhere else in the UK put together. I have a nagging worry that I’ve unwittingly contributed to a similar situation in the digital sphere.

I’ve found at least 300 scholarly publications citing OBO, so it’s certainly made its mark on academic research. Beyond academia, it’s directly generated family histories, novels, radio and TV dramas and documentaries. But what impact has it had on digitising crime history? 10 years on, vast swathes of our criminal records remain untouched by the digital. And while there has been large-scale digitisation of sources that crime historians use, not much of it is freely accessible, and little of it has been done by or for us.

A number of historians over the years have worried that OBO skews attention – and resources – disproportionately towards London and the higher courts, representing a tiny minority of prosecuted crimes and policing. As the digital historian and project manager, I’m thrilled to learn of young researchers who chose history of crime because of OBO. But my other half, the archives researcher, is more ambivalent.

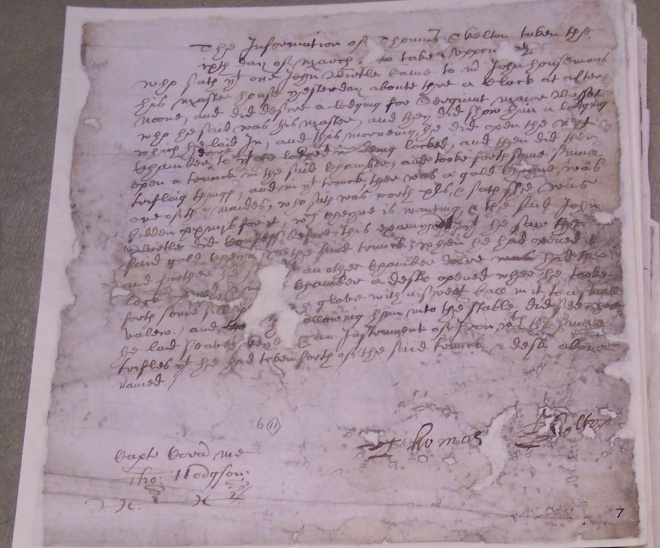

Early modern court archives aren’t like our neatly packaged, readable trial reports. They’re unwieldy, often dirty, fragmentary, intimidating in overall scale. Documents vary hugely in size, structure, handwriting, materials used and condition, defying any ‘one size fits all’ approach to digitising. They’re frequently written in heavily abbreviated Latin, or ponderously legalese-d English, or an unholy mix of both.

Who would want to struggle with that if they can use something like OBO instead? Would I, if I were a PhD student now? And how much easier is it to turn to OBO for immediate digital rewards than to start new digitisation projects with such awkward and intractable material?

I was asked to introduce themes and challenges that I think are important for the future of digital crime history. So here’s the first challenge: improving digital access to documents like this, and the hundreds of thousands like them in our archives. A second challenge: as always, how to pay for it and sustain it in the long term. And a third is the digital skills we need: I don’t mean necessarily programming, but understanding something about various kinds of code, how to work with digital data, how to work with people who do programme.

And then there are two themes I want to emphasise, that can help us to face the challenges: the need to re-use, recycle and share digital content; and the importance of collaboration and partnerships.

Re-use

I’ve blogged recently about the dual identity of the Proceedings; ideal for quantitative analysis, which needs a structured database; but also containing many rich, engaging witness narratives that demanded full text. The solution found in OBO’s case was to transcribe using a double-rekeying process that’s less accurate than traditional standards for scholarly editions, but far more accurate than OCR, and then mark up transcriptions with XML tags to create structure that can be extracted and turned into a database.

There are certainly downsides to this: time-consuming, expensive, unwieldy. [Both Tim and I agreed in the subsequent discussion that we wouldn’t try to do it quite like that today, though I’m not sure we’d be in complete agreement on exactly what we would do instead…]

But the upsides: accuracy, completeness, versatility.

Having created our digital data, it can manipulated and re-used in many ways. Convert it into other formats. Index it in different ways for different kinds of search. And even transform it with new markup for different purposes, as in Magnus Huber’s Old Bailey Corpus Online. There have been uses of OBO that no one could have predicted.

Bridget: Searching in London Lives, Connected Histories, 18th-Connect (are those other results the same person?); a dot somewhere in this graph from Datamining with Criminal Intent. Same data in four places: making new connections, seeing trials in different ways.

I’d argue there are two lessons from OBO for everyone, whatever kind of project or source they have in mind:

- digitise in a way that best captures the information in a source;

- & which facilitates future re-use and collaboration

Not the specifics of transcription or markup or any particular search engine. Given that many crime history sources are heavily formulaic, or in Latin before 1733, sometimes verbatim transcription can hide as much as it reveals, make it harder to find the useful stuff. Some – many – of our sources simply don’t have rich stories to tell like OBO.

Creating data that is clean and consistent, well-structured and accurately documented may cost more at the beginning, it may require more of an investment in technical skills and management, but it will make your efforts worth more in the long run.

Partnerships

What kind of collaborations and partnerships do we need? Let’s start with the vital one: the relationship between the historians and the keepers of the archival documents. Well, I admit I’m worried about that relationship. Here’s one reason why.

Why does this resource trouble me? It’s not just because it’s behind a paywall.

OK, in an ideal world, all these resources would be freely accessible to all. But I know all too well how expensive digitisation is. Someone has to pay; it’s just a question of how. The grim reality is that archives and libraries are under intense financial pressure and it’s only going to get worse: and that one of the few reliable paying audiences outside academia is family historians.

And findmypast have made a great, affordable, resource for family historians. But it’s a terribly limited one for crime historians. It’s a name search; as far as I can tell, no separate keyword search or browse. (If I’m wrong, there’s nothing telling me so.)* The needs and priorities of family historians and academics overlap, but they’re not close enough that creating resources that can serve them both well just happens.

Then you have, say, Eighteenth Century Collections Online or British Newspapers 1600-1900, which are designed more for academic audiences, but virtually inaccessible to individuals outside academic institutions, and those whose institutions can’t afford the price tag. And even then pretty much all you can do with those is keyword search and hope what you want isn’t lost in garbled OCR text.

Both kinds of resource are black boxes that make it impossible for a researcher to evaluate the quality of the data or search results; and hinder any kind of use other than those the platform was specifically built for. And if the data is locked away in a box it can never be corrected or improved or enhanced – even though the technology to enable that is continually developing. So publishers lose out, in the end, too.

Are there alternatives to the black box?

The Text Creation Partnership is funded by a group of libraries led by Michigan. It’s transcribing content from major commercial page-image digitised collections. The resulting texts are restricted to partnership members and resource subscribers for 4 or 5 years and then released into the public domain.

The images continue to be behind the paywall, and not all texts are transcribed. For ECCO the proportion is small, but EEBO’s goal is much more ambitious: one transcription for each unique text (usually first editions). In January 2015, 25,000 phase 1 EEBO texts will become available to everyone for search and to download for textmining or whatever else we can think of by then. (Phase 2 in ?2019 will be something like another 40,000 texts.)

It surely is not beyond our wit to translate that kind of public-private collaborative model to crime records [suggestion here], and for that matter, other archival records with overlapping academic/family history user groups. But to do so, I think we need to build partnerships between historians, archivists and publishers much more than we’ve been doing. And if what you want is totally free-to-access resources, you still need to work with archivists to find answers to the ‘who pays?’ question. I hope today can be a good starting place.

‘The Crowd’

But it’s not enough simply to think about institutional collaboration.

A lot of smart people are thinking very hard about ways to facilitate collaborative user participation in digital resources – transcription, indexing, correction, tagging, annotation, linking, and they’re building tools whose usefulness often isn’t confined to volunteer projects and ‘crowd sourcing’. (The re-use maxim applies here too: don’t build from scratch if other people have already done the hard work building and testing good tools.)**

However, don’t imagine ‘the crowd’ is an easy option. OBO has been trying it out for a while and we’re only sort of getting there.

Part of our problem, on reflection, has been adding these things near the end of a project when we launch a website and then hope for something to magically happen while we go off to the next project.

A second issue has been user interfaces and design. We took a while to learn that we have to make participation easy, really easy, and we have to build the design in from early on. It’s no good building something that needs a separate login from the rest of the site, with a flaky user database that was tacked on as an afterthought. Third, and related: understand the limits of what most users are willing to do.

Two years ago, we added to OBO a simple form for registered users to report errors: one click on the trial page itself. People have been using that form not simply to report errors in our transcriptions but to add information and tell us about mistakes in the original. The desire on the part of our site users to contribute what they know is there. Just don’t think that means there’s a ready-made ‘crowd’ waiting to turn up and help you out without plenty of effort on your part.

Historians and our dirty data

And what about us, the historians who have been or are working in the archives? We’re all digitizers now, and have been for a long time. Well, sort of. My computer has folders of databases, transcriptions and (to use the technical term) “stuff” that is kept from public view because, well, it’s a mess and I never get around to the data cleaning needed and it would be embarrasing to let people see my mistakes. I’m sure I’m not alone. [There were nods and sheepish grins all round at this point. You know who you are.]

Increasingly in future, there are going to be requirements from funders to share research data in institutional repositories and the like. We should not be assuming that means just scientists! We shouldn’t in any case be doing this just because someone demanded it; it should become a habit, the right thing to do to help each other.

But we need to get the right training in digital skills for students, so they know how to make good, shareable data, and how best to re-use data shared by others. (Full disclosure: I’m working on a project to create an online data management course for historians at the moment…)

Digitisation, digital history and re-usability don’t have to be all about big funded projects. It can start with personal decisions and actions: clean up your old data, put it in your institutional repository, share it with a Creative Commons licence, tell your colleagues and students it’s there. Relinquish some control. [more thoughts on this]

If we digitise for re-use, and re-use to digitise, we can share and collaborate, and build partnerships that can make some of the challenges of digitisation less intimidating. Digital history should be an iterative, accumulative, learning process rather than one-off ‘projects’ to be ‘launched’ and then left to gather dust.

—-

* The findmypast resource has only gone up recently and the content isn’t complete yet. Keyword search functionality is apparently supposed to be included in the resource and it’s possible that will become available as it rolls out. But it should be noted that even a keyword search is unlikely to fulfil the needs that crime historians often have to crunch numbers in complex ways.

** The tools and projects in this slide really are a tiny sample of what’s happening now. They are:

- From Cursive To Database http://freeukgen.github.io/FromCursiveToDatabase/

- T-PEN http://t-pen.org/TPEN/

- Transcriptorium http://transcriptorium.eu/

- Marine Lives http://www.marinelives.org/

- The arcHIVE http://transcribe.naa.gov.au/

- Open Source Indexing http://opensourceindexing.org/

(If you’re on Twitter and you want to know more about this, there are three people I think you really ought to be following as a starting point: @benwbrum, @mia_out and @ammeveleigh.)